I grew up in Southern California, famous for its Hollywood movie stars, tangled network of freeways, and earthquakes. Somehow, I’d escaped earthquakes for the first ten years of my life, even though the San Andreas Fault line runs a stretch of over 800 miles.

It begins in Mendocino north of Sacramento, through the Santa Cruz Mountains and the San Francisco Peninsula, along the base of the San Gabriel Valley Mountains near my hometown of South El Monte, and all the way down south to the Salton Sea in the Imperial Valley desert.

The San Andreas Fault misses the city of Los Angeles by about thirty miles, but it’s ten miles deep—a massive crack in the earth—building up pressure, ready to erupt into The Big One any day, when California will split off from the rest of the United States and then washed over with an enormous tsunami. Los Angeles will not be spared. At least, that’s what the movies want us to believe.

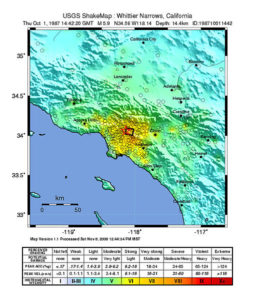

While we waited for The Big One, a never before discovered fault called the Puente Hills thrust system, surprised us with the Whittier Narrows Earthquake at 7:42 in the morning on Thursday, October 1, 1987. This precise date and time is etched into my mind forever.

It was only a 5.9 magnitude quake, but it was the largest one to hit Southern California since the 1971 San Fernando Earthquake, more famously known as the Sylmar Earthquake.

The Morning of the Earthquake

It was a muggy, unusually hot morning—later on, I’d learn from my mother that we were having an Indian summer, and this was a telltale sign of an impending earthquake.

I was brushing my hair in front of the living room mirror because my mother was in the shower, and we only had one bathroom. This was the daily morning routine.

I was in Mrs. Gutierrez’ sixth grade class at Epiphany Catholic School, so I was wore a light blue uniform blouse with the stiff collar under my blue and gray plaid jumper, which draped over my body, instead of cocooning the sprouting curves on my female classmates’ bodies. I’d skipped the second grade, and no matter what I did to my hair, the only thing I could control, I still looked like a lanky, flat-chested, buck-toothed ten-year old.

As I brushed my hair into a simple ponytail, I thought about how much I dreaded school, not because it was too difficult, but because it was too easy with our outdated textbooks, the routine reading aloud and filling out the exercises at the end of the lessons and chapter. I knew there was more to learn at the museums of art and natural history, at the libraries, shelves full of Ray Bradbury and Judy Blume, because I was drawn both to science fiction and the dirty secrets of pre-adolescence, at the music conservatories filled with the reverberations of violins, at the arboretums with exotic jungle vegetation and whimsical English gardens.

I thought about how lonely and dull life was in South El Monte, California, where I preferred to stay in my bedroom, especially after the rare rainfall, opening the wooden framed hung sash window original to the 1950s construction of the house, letting in the cool air and gray skies. I identified with characters such as Anne of Green Gables and Pippi Longstocking because they were outsiders, but they still managed to find their little tribe of kindred spirits.

And so it was at 7:42, on the morning of October 1, 1987, when the Puente Hills thrust system erupted through the earth’s crust, a fault never known before to the Caltech scientists, violently shaking the house, because it was the kind of earthquake caused by what they refer to as a double train of P-waves. It really did feel as if two steam engines rumbled through the living room—the loudness of the earthquake was just as horrifying as the shaking.

It was later nicknamed the Whittier Narrows Earthquake, as the epicenter was close to the sprawling park and nature area by the same name. Whittier, Alhambra, and Pasadena are frequently mentioned in stories about the earthquake because that’s where most of the damage happened. But Whittier Narrows is located in Rosemead, the neighboring city to South El Monte, and the epicenter was just three miles from my parents’ house.

Seismologists say that in a few cases, the epicenter suffers the least damage, where the point of rupture is far below the surface. In those cases, the area that suffers the most damage is the point where the fault line bursts through the surface. But the Puente Hills fault line that shook Southern California on October 1, 1987 wasn’t far below the surface. We were spared physical damage, but there are other types of destruction that can’t be seen.

One moment, the reflection of the living room in the mirror stood still, and the next, it trembled back and forth in quick motions, like a scene inside a snow globe when it’s being shaken. All the wood in the house grinding, the glass rattling, and the insides of the earth threatening to burst through the house’s foundation. I looked in the mirror, and then I looked behind me—my mother stood nearly naked in the hallway, half wet from taking a shower, shouting “earthquake” and directing my brother and I to take cover.

At school, we were taught to crouch underneath our desks with our hands clasped behind our necks to protect our spinal cords. It always seemed ridiculous at the time, but most of us secretly enjoyed the drills because it meant a break from the classroom lessons. We didn’t have school desks at home, but I remember the teachers standing in the doorways, so I stood in the kitchen doorway while my brother stood in the doorway of his bedroom.

Aftershocks

In those thirty seconds, my life changed forever. I think most kids were able to calmly go back to school the next day, and perhaps they even enjoyed the day of the earthquake because they didn’t have to go to school. After the tremors stopped, I sat on the floor underneath the dining room table, terrified that it would shake again. My only consolation that day was knowing my father was safe and trying to make his way back home from downtown Los Angeles.

When I wouldn’t come out from underneath the table after several hours, my mother kept thinking of different ways to assure me everything would be okay. At one point, the teenage girl from across the street, Tina Chavarria, stopped by and offered to let me hang out with her.

That solution finally made sense to me. After all, the earthquake had happened in my house—surely, I’d be safe anywhere but home. Most of all, I wanted to get away from the memory of the rattling mirror, of my mother unclothed in the hallway, vulnerable and scared in a way that I had never seen before. No matter how much my mother tried to keep me safe, she couldn’t keep the earth from shaking.

Tina entertained me for a few hours until my mother decided that we’d imposed enough, plus my father would be getting home soon, and we needed to get on with our lives. No one’s house had fallen, at least, not in our neighborhood, and there wasn’t so much as a crack in the wall or a broken glass. Really, we were fine, and a 5.9 earthquake isn’t so bad in the grand scheme of things.

But that night, I lay awake, unable to fall asleep, in my bedroom—my perfect bedroom with the displays of miniature tea sets, dolls and books neatly arranged on the shelves by size and alphabetical order. I don’t know what gave me the idea, but I felt the tip of one of my eyelashes, and it felt good to pull one. So I pulled another and another, and I don’t know how many I pulled, but the next morning, I looked in the mirror, and I could see obvious gaps.

My mother noticed it almost immediately, and then it seemed like everyone else noticed it, too. At school, I was delivering something to the principal’s office with a classmate, and she asked what was wrong with my eyes. I looked away from her, and I said my eyes were itchy.

Even though I was embarrassed, I kept pulling my eyelashes, and I hid the damage by making minimal eye contact with the world. Pulling my eyelashes was the only way I knew how to tame the fear. I was terrified of being in tall buildings or brick buildings. I was terrified of cracks in the driveways. I was terrified of creaking sounds in the walls. I was terrified of dogs barking for no reason. I was terrified of hot, quiet weather—Indian summer weather that my mother still swears is a warning sign of an earthquake. I was terrified of being alone, and that fear would come back to haunt me as a grown up in adult relationships.

I stopped brushing my hair in the living room mirror. The bathroom seemed safer, plus I could listen to the little radio in there to drown out the thoughts in my head. One morning, while I was brushing my hair, Carole King came on with “I Feel The Earth Move” and I wondered if she’d secretly been thinking about earthquakes when she wrote that song.

Years later, when I was sixteen years old, I understood what Carol really meant, when I fell in love with a boy who was a year older than me. By then, my eyelashes had fully grown back. It was an intense romance, making me feel as if the earth was indeed moving under my feet and the sky tumbling down. And there would be more boys and then men— all shaking the foundation of my life each time, until I crumbled apart like a building in an earthquake. In 2003, I was twenty-six years old, trying to escape a deteriorating marriage, and I began pulling my eyelashes again.

I’d like to think that was The Big One of my life in 2003, when all the pressure building up in the fault lines of my life was finally released. There have been aftershocks since then, and maybe new earthquakes, but I’ve gotten better at swaying with the tumultuous movement. I don’t have terrible eyelash pulling episodes like I used—they are here and there, and fairly minor in comparison.

They say that the buildings that fare the worst in earthquakes are the ones that are built too rigidly. I’ve learned that you can’t stop the earth from shaking. So you shake along with it.

This was beautiful. It’s funny how the things that affect us so deeply may have no impact on others.

Just saw this somehow and it really touched me. Thanks for writing.