“C-section babies are born with perfect heads,” my boss at the time would say. She knew I’d been dreading a C-section and would say this to reassure me.

When Lucia was six weeks old and finally breastfeeding, I began to notice that when she’d lay on her left side, she looked like a normal baby with a flawlessly shaped head, a proportionally placed eye and ear, and a well-rounded cheek. But when she’d lay on her right side, the left side of her head looked a little off: a slanted forehead, a slightly twisted ear, her cheekbone flatter and the area around the eye stretched out.

Mind flipping through memories like thumbing through a card catalog at the library, back to the days after Lucia was born. Red marks on her forehead. “Why where there red marks on Lucia’s forehead?” I’d asked the obstetrician. Forceps. I clearly remember he said something about forceps.

Weren’t C-section babies supposed to have perfect heads? Weren’t forceps only supposed to be used when the baby was stuck in the birth canal? This was like taking a shortcut to avoid the car accident and getting into the car accident anyway.

Three weeks earlier, a lactation consultant had made a home visit to help me figure out how to get Lucia to latch and breastfeed. The prognosis was grim.

“Her body seems more floppy and low tone than most babies. Her jaw is shifted slightly to the left and it seems that the cranial bones elongate upwards towards the right just a bit. The back of the skull extends back and up a bit too.”

I had no idea what to do with all the information she’d given us. She suggested taking Lucia for osteopathic style body work. But when my husband, Daniel, and I mentioned this to the orthopedist, at Lucia’s follow-up appointment to check on her broken leg, she rolled her eyes, equating it to some type of voodoo. A lactation consultant! Ha! What would a lactation consultant know about such things! Leave this kind of work to the doctors. The experts. Yep. Doctors don’t care much for midwives or lactation consultants.

We decided that even if osteopathic manipulation didn’t help, it certainly couldn’t hurt.

The osteopath confirmed Lucia had a misshapen head and facial asymmetry, as well as torticollis, which explained why she kept her head turned to the right nearly all of the time. Another medical condition to the list! Another specialist to see down the line, a physical therapist.

Final diagnosis: plagiocephaly, a flattening of the head, caused by being breech, made worse by the torticollis, which was also caused by being breech, along with the use of forceps.

Collect them all! the universe was saying. Breech baby. Check! Emergency C-section. Check! Placental tear. Check! Broken leg at birth. Check! Breastfeeding problems. Check! Laryngomalacia. Check! Sacrococcygeal teratoma. Check! Torticollis. Check! Plagiocephaly. Check! Keep ‘em coming, I thought, at this point, was there ever going to be a stop to the madness? This was an epic curveball symphony!

Her pediatrician agreed it was plagiocephaly. The neurosurgeon who saw her for her teratoma also agreed it was plagiocephaly. We were even referred to a craniofacial plastic surgeon who confirmed her diagnosis as plagiocephaly. He recommended we take her to get fitted for one of those little helmets, and then he asked the nurse to instruct us on different ways we could position her in her bassinet so she wouldn’t lie on one side of her head for too long.

Plagiocephaly. Flat-head syndrome. So many babies had it these days, we were told, since the big scare about sudden infant death syndrome—babies had to sleep on their back, so they were getting flat heads. No big deal. Some babies even outgrow it.

All of this happened while we were living in Arlington in the Dallas-Fort Worth area. Shortly before we moved to San Antonio in November 2017, we’d switched to a new pediatrician. Lucia was starting to lift her head, and we were beginning to think maybe her head shape was improving just a tiny bit. A semblance of normalcy around the corner, perhaps?

Her body seems more floppy and low tone than most babies. The lactation consultant’s diagnosis echoed in the back of my mind. Lucia was still rag doll like in her posture. There’s a picture of us with our friend and her baby (who was only two and half weeks older than Lucia), her baby sitting up straight in her arms, Lucia’s head falling backward into my arms. Lucia was five months old.

The new pediatrician referred us to a neurosurgeon and a neurologist. Because we moved, we had to start the referral process all over again, and in February of 2018, we finally got to see these new specialists in San Antonio. Within the first five minutes, the neurosurgeon felt Lucia’s head and told us it wasn’t plagiocephaly. She asked us when her sutures had closed. We had no idea! This wasn’t in any of the new parent guides we’d been given.

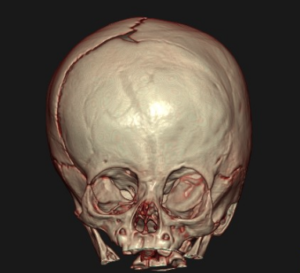

No, Lucia didn’t have plagiocephaly. She had craniosynostosis. There are different kinds: metopic, saggital, lambdoid, and coronal. She had unilateral coronal craniosynostosis—the suture on the left side of her skull had closed. I asked her to repeat it several times. I asked her to write it down. When we left that appointment, for several weeks after, I still couldn’t pronounce it.

“Craniosynostosis (kray-nee-o-sin-os-TOE-sis) is a birth defect in which one or more of the fibrous joints between the bones of your baby’s skull (cranial sutures) close prematurely (fuse), before your baby’s brain is fully formed.”

—Mayo Clinic

Her jaw is shifted slightly to the left and it seems that the cranial bones elongate upwards towards the right just a bit. The lactation consultant’s diagnosis cut forward through time. She’d known something that no other doctor, up until now, was able to catch.

If pronouncing it wasn’t hard enough, the description of the surgery to correct it was like something out of a Frankenstein horror movie. Cranial vault remodeling (CVR), or more specifically, a fronto-orbital advancement (FOA). The surgeon sat there, matter of fact, explaining the procedure: they make a ziz-zag incision from one ear to the other across the top of her head, remove part of her skull, reconstruct it, and then screw it back on. I felt numb all over again, like the night she was born when I was given a spinal.

One more curve ball from the universe! Keep ‘em coming. One in two thousand babies are born with this condition. Oh yes, I was on the wrong side of statistics. What were the odds of having a placental tear from the external cephalic version? Less than one percent. What were the odds of Lucia being born with a sacrococcygeal teratoma? One in thirty-five thousand. Or maybe I’m looking at all of this the wrong way. Maybe I should start playing the lottery.

How could so many doctors have missed this? Maybe I’d gotten too good at hiding it. “Take a picture of her good side,” I’d always tell Daniel. I’d gotten selective about only sharing photos taken of the right side of her face, or even the front side of her face, although her left eye always looked a little larger. No one could tell she had a funny shaped head. Or everyone pretended not to notice.

Oh, it’s common to misdiagnose craniosynostosis as plagiocephaly, we were told. And Lucia’s presentation of craniosynostosis wasn’t so physically obvious. The only way to truly diagnose it is a CT scan. If it had been caught earlier, she would have been able to get the less invasive “endoscopic” surgery. But it was too late. There was nothing we could do to avoid another major surgery. Far more major than the one to remove her teratoma.

We had no choice. The surgery is necessary to allow adequate space for Lucia’s brain to grow and develop properly. Not doing the surgery, despite the small risk for serious complications, was far worse. Would you blame me if I’ve developed an aversion to the small chance of complications?

We’ve spent the last several months researching craniosynostosis, joining online support groups, and reading stories about other parents going through the same thing we’re going through. A similar story keeps popping up: they were told their baby had plagiocephaly. They’d been misdiagnosed. But many of us had that nagging feeling that something wasn’t right. So we kept asking them to look at our babies’ heads. That’s how we eventually learned our babies had a thing called craniosynostosis. (We call it cranio for short.)

Lucia is one in two thousand. Some days, I’m feeling confident the surgeons will do a spectacular job because western medicine can be wonderful that way—that Lucia will be like most of the babies who’ve had this kind of surgery and grew up to have normal kid lives. Other days, I am terrified and exhausted, imagining what it would be like to have her skull cut open. I’ve had anxiety dreams about it.

Some days it still doesn’t feel like any of this is real. Maybe all of it has been a bad nightmare, from the laryngomalacia to the craniosynostosis. But her surgery is on our Google calendar, set for July 17, 2018, at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston—ranked as having one of the top craniofacial centers in the United States—where we’ve decided she’d get the best treatment. After battling it out with health insurance (we lost – hospital out of network), we were fortunately approved for financial assistance. Otherwise, we would have been at least $75,000 out of pocket.

The days are now simultaneously too long and too short, as I try to hold onto every minute of Lucia before she has to go into that operating room, holding her in my arms, burying my face in her long, unruly hair, smelling of sweat and sweetness, wishing time would fast forward to one day in the future, when I can look back, knowing that everything turned out just fine, and we’ll never have to set foot in a hospital again.